Parasite: How Metaphorical

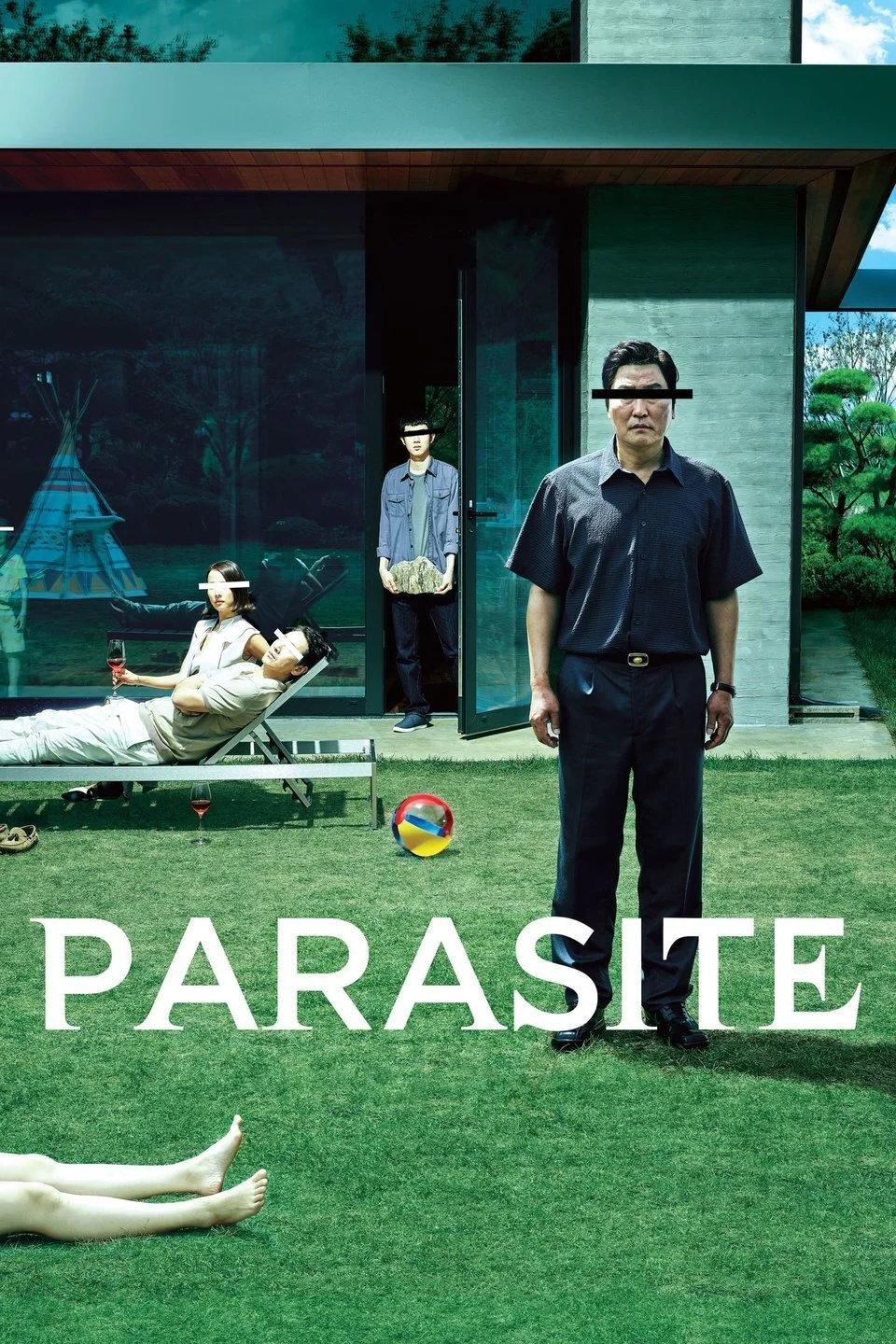

Before I had even watched the film, I found the first images of Parasite’s marketing to be very peculiar.

On a poster is the family who would later be known to me as the Kims, consisting of our main “heroes”— a father, mother, sister, and brother; Ki-taek, Chung-sook, Ki-woo, and our entry point into the film’s semi-basement, Ki-jeong, respectively. What was so striking to me about the image was that each character in the poster had a blackbar masking their eyes.

If the blackbar was removed, they would be looking out past the image, and directly at you. Chung-sook and Ki-Woo even cock their heads in a strange anti-pose, as if they caught a glance of you peeking at them, invading their privacy through an invisible candid camera. And considering that pair of pale legs lying in the left hand corner of the image, it seems like you didn’t walk in at a great moment. The image unsettled me and spiked levels of curiosity that I hadn’t felt about a movie poster in a long time— a cypher begging to be cracked. I waited for the film's release to have my hand at unraveling the image. I like to think that I figured out the significance of the blackbars pretty early. My reading was the same one that I assume many people would have probably obtained had they cared about the blackbars in the same way I did (I can't imagine this sample size to be very large, though).

When individuals think of groups in terms of class, I feel they tend to use terms like “the poor” or “the one percent”. Because these characters eyes are covered by a blackbar, obviously there is a sense of anonymity or a loss of identity that comes with seeing the world through the lens social classes. After watching the film, it's clear that characters are clearly divided into two teams, rich and poor; the story concerns class matters as well— hence blackbars over the eyes to signify this theme. It’s the best I could come up with, and if it wasn’t correct, I was satisfied with my guess. What I wasn’t satisfied with, however, was a lingering feeling that there was still some detective work to be done. Something was missing. So I watched it four more times.

Parasite acts like a living, breathing organism. With every event in the film, you feel the movie ebb and flow, evolve into whatever it needs to be to continue on. To survive. The meshing of genres, from comedy, thriller, drama, horror, is seamless— alien, even. The experience of watching the film for the first time is akin to discovering a new species, and watching it from afar. How it moves, how it sleeps, how it kills. And oh, boy does it kill. But just like a wild animal encounter at the zoo, viewers are placed at a safe distance. These are not people I know. This could not happen to me. For American audiences, not only is the movie foreign in terms of its country of origin (Korea), but in its execution. From his filmography, it’s clear that what Bong Joon Ho intends for all of his films is some element of social satire. And his satire has never been as sharp as Parasite. In a way, it becomes a doubled edged sword. With all of the clockwork precision and construction in the film, there are elements that suffer slightly— the characters, the pathos. Though it attempts to regain some humanity in way of a Hail Mary pass during the last minutes of the film (maybe added in a latter draft), the film still remains as it was intended— a single celled organism, contained and ever evolving though the eyepiece of a microscope.

In lieu of the metaphor, the characters act as limbs to the body of the film. They allow the film to move forward whether it be by way of their intuition, their clumsiness, their desperation, etc. Both families involved, the Kims and the Parks (their rich counterparts), click the movie along mechanically. Score, sound design, cinematography, even the writing all work as different parts of Bong’s creature— a kidney here, a brain there, some lungs maybe. Parasite's heart, however… That's what I was trying to find during and in-between my quintuple viewings of the movie. And thinking back to the blackbars over the character’s eyes in the film’s poster and my strange yearning for the discovery of meaning in each symbol, I had an interesting thought.

At points during the film, Ki-jeong (the son) exclaims “how metaphorical!”. I thought it to be a throwaway catchphrase, and a great way to characterize his eagerness and excitement as he correlates his family’s rise in social status to random lucky objects and coincidences happening around him. Thus, Ki-jeong acts as this walking ideology: Evolving with and following happenstance will eventually lead to happiness (simply put, go where the wind blows). But, what he means to say when he utters “how metaphorical”, is actually “what a coincidence”. And it is the belief and obsession with metaphor that causes much of the families’ troubles.

At the heart of Parasite is not the significance of a blackbar, a deep read of a symbol, or images to be examined on a poster. At the center, is the idea that metaphor is deadly, and can lead to doom if blatantly thrown around. There are plenty of symbols and images in the film that can be speculated upon— a rock, a peach, a dark shadow in the corner of a drawing. Its ambition, genre bending, and satire make Parasite a good film. However, what makes it a great film is its ability to lure audiences into a world with never-ending symbolism and mystery, forces them to consider all of it. With Parasite, Bong Joon Ho crafts a truly impossible, endless puzzle box. A film that plants a seed, lingers in your brain, wiggles deep down, and empties out your pockets five times over— a parasite.

How metaphorical.